Sentence-final particles (SFP’s) in Japanese sentences, though they come last, carry incredibly important information regarding the emotional content of the message. As a response to an offer, they can make “good” mean “I’m fine” or “that would be great,” embodying the difference between a no and a yes. While they are vital to expressing an attitude towards a statement, they can also be used to construct a certain linguistic identity. SFP’s are, in fact, a large part of what makes masculine language masculine and feminine language feminine.

While popular ideology and past research has conceptualized the set of SFP’s as containing men’s particles, women’s particles, and neutral particles, this study looks at a corpus of Twitter posts cross-referenced to blogs where users self-identify as male or female to demonstrate that the reality is more complex. In fact, no SFP is limited to exclusive use by males or females. Instead, this study takes a third wave sociolinguistic perspective and demonstrates that while there are differences in frequency of use of some SFP’s, any particle can be used by any person in a tweet as a part of their construction of identity and performance of gender in an online community that puts the focus on language.

Previous Research

Sentence-Final Particles in Japanese

In any conversation, there are gaps between the semantic content of the utterances and the meaning that is intended to be inferred therefrom. This is a central tenet of the Relevance Theory of pragmatics (Sperber & Wilson, 1987), which posits that speakers will be as economical as possible in conveying a message and that listeners, when searching for meaning, will presume each utterance’s relevance and infer the unspoken meaning from context. This gap between spoken words and intended meaning is especially significant in Japanese, a language which is sometimes seen by cultural outsiders as indirect to the point of being incomprehensible (Fengping, 2005). This gap must be filled by inference on the part of the listener, a task that SFP’s can assist by conveying the attitude of the speaker toward what they are saying.

While SFP’s vary dialectally and on the fringe include any number of neologisms and slang forms, the standard ones have been catalogued and defined in various ways. Some analyses are simple lists of functions (NLRI, 1951), others like Reynolds (1985) place them in categories such as declarative, confirmative, and dubitative and rank them on a scale of assertiveness, and still others comprehensively describe their meanings as stemming from governing pragmatic principles (Kose, 1997). These standard SFP’s number as follows.

よ (yo)

The NLRI (1951) lists four functions for yo: (a) to persuade

the addressee, (b) to reproach the addressee, (c) to strengthen a command, and

(d) to strengthen a suggestion. Reynolds (1985) categorizes

yo as a declarative particle that ranks fairly low on the assertiveness scale.

Kose (1997) argues that yo reflects the speaker’s personal commitment

to the proposition — that they are willing to be held responsible for the content

of the message. This means that the speaker believes a statement ending with yo

to be true or intends to perform the action expressed by a directive ending with

yo.

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | yo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“Taro sings well, (I tell you)” (Kose, 1997, p. 1)

ぞ (zo)

Reynolds (1985) states simply that zo functions as a stronger

version of yo---its position on her assertiveness scale is higher---whereas

Kose (1997) says the particle indicates fundamentally that the speaker

wants the addressee to agree with them, or to believe that the sentence ending in

zo is true. The NLRI (1951) notes that zo can threaten or warn

the addressee. zo also has a varient form ze, which is functionally very similar

if not the same.

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | zo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“Taro sings well, (damn it)!” (Kose, 1997, p. 1)

ね (ne)

Analysis of ne is perhaps the most difficult because the SFP seems at first to

have contrary meanings. It can function somewhat like a tag question, indicating

the speaker’s belief that the addressee knows better than they do about the

proposition, as in Example 3, but also to elicit empathy as in Example 4 or to

soften a request or command as in Example 5. Reynolds (1985)

captures the tag question effects by classifying it as a confirmative particle,

while Masuoka (1991) argues that ne is used when the speaker

and the listener share knowledge and intention. Kose (1997)

synthesizes the many uses and explains that ne is in some ways the counterpart

to yo, reflecting the speaker’s belief that the addressee is committed to the

message — that they believe a statement to be true or intend to act on a

directive. If ne is used with rising intonation, then it reflects that the

speaker supposes rather than believes the addressee to be committed.

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | ne |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“Taro sings well, doesn’t he?” (Kose, 1997, p. 1)

| boku | wa | mita | koto | ga | nai | ne |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg | TOP | see-PAST | event | NOM | exist-NEG |

“I’ve never seen it before” (Kose, 1997, p. 91)

| namae | o | kaite | kudasai | ne |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | ACC | write | do me a favor |

“Please write your name” (Kose, 1997, p. 90)

な (na)

Suzuki (1990) argues that na is a contrasting particle: it indicates

that the speaker believes what they are saying to be different from what the listener

believes, or perhaps what is generally believed. In this way, it functions similarly

to an English sentence with primary stress on the first-person pronoun I, and thus

can connote an introspective feeling. Reynolds (1985), to

similar effect, classifies it as a declarative particle with a higher

assertiveness score than yo, since it can make some claim about the

addressee’s mental state, but less than zo because it does not express a

desire to change it.

| ano | hito | ni | wa | sootoo | sekinin | ga | atta | to | omoo | na |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| that | person | LOC | TOP | substantial | blame | NOM | exist-PAST | QUOT | think |

“**I** think that guy was pretty much to blame.” (Suzuki, 1990, p. 318)

わ (wa)

There are two kinds of wa as an SFP: one with a rising intonation which is

characteristic of women’s speech, and one with a falling intonation which can be

used by anyone. It has been argued that rising-wa has more emotional emphasis

(McGloin, 1997), but it is not clear to what degree they are

essentially different or to what degree the difference is actually a result of

the fact that the former is stereotypically feminine. The NLRI (1951) makes no mention of the difference, but says that the particle expresses

surprise. Kose (1997) clarifies this, saying that wa is used

when the facts of the sentence have just become apparent to the speaker.

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | wa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“Oh, Taro sings well!” (Kose, 1997, p. 1)

さ (sa)

Suzuki (1990) describes sa as lending a flavor of obviousness

to a generalization. In other words, sa indicates that the speaker believes that

everyone believes the proposition to be true, and doesn’t expect any argument.

| Nihon | tte | soo iu | shakai | nanda | shi | sa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | TOP | that kind of | society | COP | so that’s why |

“As you know, Japan is that kind of society, so that’s why” (Suzuki, 1990, p. 317)

Nominalizing particles

No and mon are two particles which grammatically function as nominalizers,

changing sentence predicates into noun phrases. Accordingly, in the sentence

final position they have the pragmatic function of softening the bluntness of a

statement. Furthermore, they can be followed with yo, ne, or sa for a

combined meaning.

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | no |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“It’s that Taro is good at singing.”

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | no yo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“It’s that Taro is good at singing, I tell you.”

Dubitative particles

Ka is, by itself, the quintessential dubitative particle (Reynolds, 1985); it is the standard way of forming a question in Japanese.

Two variants, ka na and ka shira, the first which is followed by the

contrastive particle na and the second by an abbreviated form of shiranai

(don’t know), both convey a meaning of “I wonder.” Furthermore, since ka very

directly solicits an answer, it can be seen as too blunt for casual discourse.

In those cases, the nominalizer no with a rising intonation can function as a

question particle.

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | ka na |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“I wonder if Taro is good at singing.”

| Taroo | wa | uta | ga | umai | no? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taro | TOP | singing | NOM | skillful |

“Is it the case that Taro is good at singing?”

Gender Differences in the Use of Sentence-Final Particles

Since the nationalizing language standardizations of the beginning of the twentieth century, the Japanese have been intensely interested in the workings of their own language. Scholars in kokugogaku, the national language studies, have emptied many inkwells classifying and describing aspects of the Japanese language, focusing especially on the differences between men’s and women’s speech.

Ide (1979) collected data about the use of SFP’s by Tokyo college students and found that many of them strongly correlate with the gender of the speaker. Her results are presented below, classified as particles used primarily by men, those used primarily by women, and those used by both men and women.

- Particles used predominately by men

mon nanasayo nazezo

- Particles used by both men and women

ka namonnenoyoyo newa newa yo

- Particles used predominately by women

ka shiramon neno?no neno yowa

The particles used by both men and women are also the most commonly used

overall: yo, ne, and their combination are the most standard SFP’s, and are

licensed even in grammatically polite[^1]

sentences. Polite forms, which are used when speaking to people with whom one is

not close, correlate with situations in which expressing one’s personal opinion,

a function of many SFP’s, could be seen as inappropriate. Logically, the two

particles ranking lowest on the assertiveness scale of Reynolds (1985) are the most appropriate for these formal situations and

are used by both men and women.

The Japanese honorifics system has two axes: deferential, forms which index a hierarchically vertical relationship between the speaker and the referent, and polite, which index a social distance between the speaker and the addressee.

After the rise of feminism in Japan in the 1970’s, when the women’s liberation movement began to fight against the oppressive force of cultural expectations regarding women’s language, Jugaku (1979) provided a theoretical framework which Yukawa and Saito (2004, p. 26) compare in significance to Robin Lakoff’s Language and Woman’s Place

(1975). Jugaku’s analysis is tripartite, focusing on (a) language for a female audience, (b) topics chosen for a female audience, and (c) linguistic strategies used to display that the speaker is a woman. Citing historical attitudes about a woman’s place in Japanese society and women’s magazines which deal in banalities on superficial matters, Jugaku argues that women’s language, and the expectation that women speak in that way, are forces of oppression.

This oppressive force is reflected in the SFP’s that are traditionally used more

by women. While Ide (1979) finds that both genders use the

basic nominalizers no and mon equally, they are preferred by women as

complexes when they function to soften the effect of an assertion (no yo), an

assumption that the addressee agrees (no ne, mon ne), or a question (no

with rising intonation). Women being expected not to assert, assume, or

question, these softeners may be culturally conditioned. Similarly,

Ide (1979) finds that wa, which marks a sudden realization, is

also used primarily by women; perhaps men are less likely to admit surprise. With

regard to the dubitative particles, a similar pattern is seen: while both men and

women use the form of “I wonder” which contrasts the speakers doubt with the common

knowledge, ka na, only women use the form ka shira, which stems from “I don’t

know”.

In contrast, only men use the more assertive particles na, which claims a

different opinion than the norm even when softened by a nominalizer, and sa,

which marks obvious generalizations. The particle zo and its varient ze,

too, are characteristic of men’s speech. It is a result of the cultural

inequality women believe that they are expected not to impose their beliefs on

others, and thus don’t use zo when speaking to other people (Kose, 1997, p. 61). Only when she is not interacting with others but

rather speaking to herself, as in the example below, can a woman use zo.

| konban | peepaa | o | kaki | ageru | zo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tonight | paper | ACC | write | finish |

“I’ll finish writing the paper tonight (for sure!)” (Kose, 1997, p. 63)

Jugaku’s (1979) analysis shows women’s

language to be both detrimentally influenced by societal expectations on women,

but also a volitional performance of femininity. As strong as the societal

expectation that women speak and act deferentially, they sometimes choose not

to. Jugaku examines some of the innovative linguistic strategies which were

beginning to be used by women to tackle this cultural ideology: for example, she

describes schoolgirls referring to themselves as boku, a pronoun which is

traditionally used only by boys and men, to limit boys’ exclusive place in the

men’s world.

Okamoto (1997) finds that women are doing much of the same with their SFP use: although there are language ideologies in place regarding which particles are suitable for use by men and by women, it is becoming more normal for women to disregard this. In 1997, female college students used moderately masculine forms more often (18% of all SFP’s) than feminine SFP’s (12%), and even used strongly masculine forms on a limited basis (1%). This change is especially evident in comparison with middle-aged women, whom Okamoto found to use feminine forms at a substantial rate (36%), moderately masculine forms at a low rate (12%), and never to use strongly masculine forms. In fact, the instances when college students used strongly feminine forms were predominately when quoting older women.

On the internet, where “no one knows that you’re a dog,” or a woman as the case may be, unless you tell them, the cultural ideology holding up the expectation that women speak in a certain way may be all the more weakened. Although on the interconnected social networks of today’s internet many people do accurately label themselves as male or female, with no appearance cues, gender has become all the more a linguistic performance. This study attempts to reveal to what degree those users of Twitter who do self-identify as male or female modify their use of SFP’s to index those genders, and to what degree that particle dichotomy is different than it once was.

Methodology

To determine the degree to which online language is used by men and women in

different ways to perform their gender identities, this research is based on a

set of posts on the microblogging service Twitter, which are inherently public

and often conversational. Making use of the freely accessible Twitter streaming

API and the Ruby gem twitter, which together allow programmatic access to

Twitter, I wrote a piece of software to “listen,” real-time, to a subset of all

tweets as they are posted. From that stream, all tweets which contain a

sentence-final particle followed by a punctuation mark were recorded.

Twitter is by its very nature a pseudo-anonymous service---while there is a system by which public figures can have their accounts verified, the vast majority of Twitter users are under no obligation to reveal information about themselves. Unlike its competitor Facebook, pseudonyms are chosen and can be changed on a whim, a non-human profile picture is a popular choice, and the service provides no standard way of displaying demographic information like gender. Twitter does offer, however, a way to add a link to one’s personal website on the profile, and many users choose to link to their personal blog, which reveals more of their personal information.

Inspired by a study which trained a natural language processing system to guess

an author’s gender from their Twitter posts (Burger, Henderson, Kim, & Zarrella, 2011), I limited

my collection to tweets from users who had linked to their blogs on the platform

run by the Japanese social media company Ameba. Styled as the compound word

Ameblo, the blogging platform is ranked by the internet analytics company Alexa

as the ninth most popular website in Japan at the time of writing. Unlike

Twitter, Ameblo profiles have a gender field which, although it is optional,

most users fill with dansei or josei, the standard terms for male and female

respectively.

I designed my software to automatically parse the Twitter user’s associated Ameblo profile for this gender information, classifying the majority of my data. In cases where the user had designated their gender non-standardly,[^2] I manually designated the user male or female, or removed the data point. After collection, the data were manually checked to ensure that only true instances of SFP’s were recorded, and statistical analysis was performed.

E.g. one user’s term onyanoko, a pun on onna no ko, girl, and nyan, the onomatopoeia for a cat’s cry.

It is possible that a dataset limited to those users who have Ameblo may not be representative of the Twitter community as a whole. However, as users who use more than one online service in concert are likely heavier and more social users, this selection bias may reveal details of conversational language use on the internet by its “natives.” Either way, one very positive outcome of the Ameblo bias is that the dataset is virtually free of the spam and commercial posts which are otherwise common on Twitter, as bots and scammers don’t tend to have blogs.

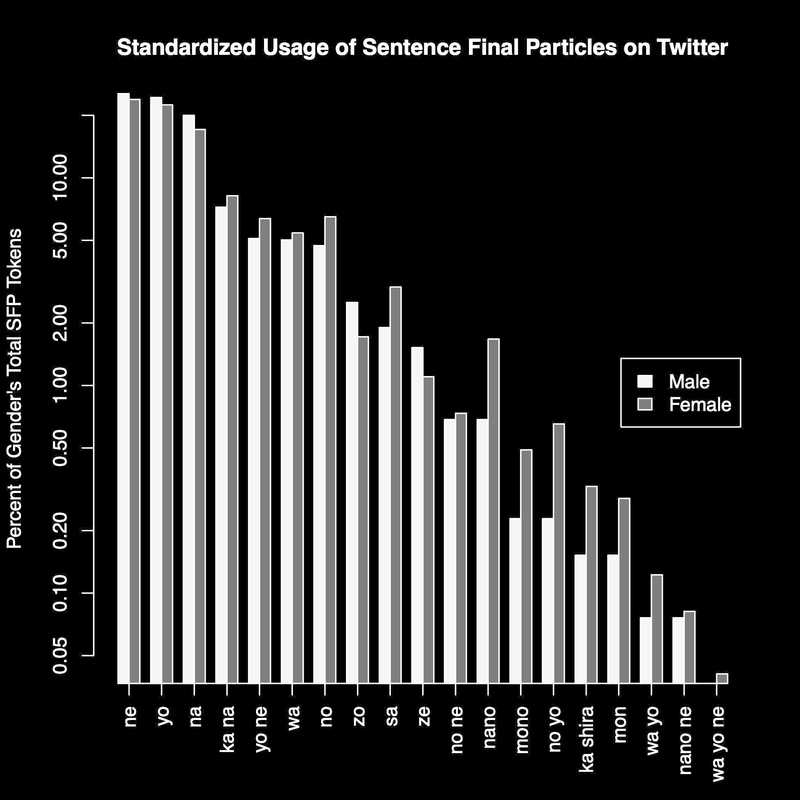

I left my software running for a few days and collected tweets containing 3767

tokens of SFP’s, 2452 posted by women and 1315 posted by men. The standardized

results are shown above on a logarithmic scale. Yo and ne, which are, as

addressed, the most acceptable for general use, constituted almost half of all

tokens for both genders. Na and ka na, which are both expressions of

introspective thought, either contrast of personal opinion or doubt, also were

well represented: na appeared around 20% of the time, where ka na formed 8%

of the tokens. The other simplex SFP’s, as well as the complex yo ne which

combines the two most common SFP’s, appeared more than 1% of the time — still a

substantial amount. The nominalizers, which represent a kind of indirectness

perhaps unnecessary on Twitter, appeared less than 1% of the time. The highly

stereotyped wa complexes and ka shira also appeared very little.

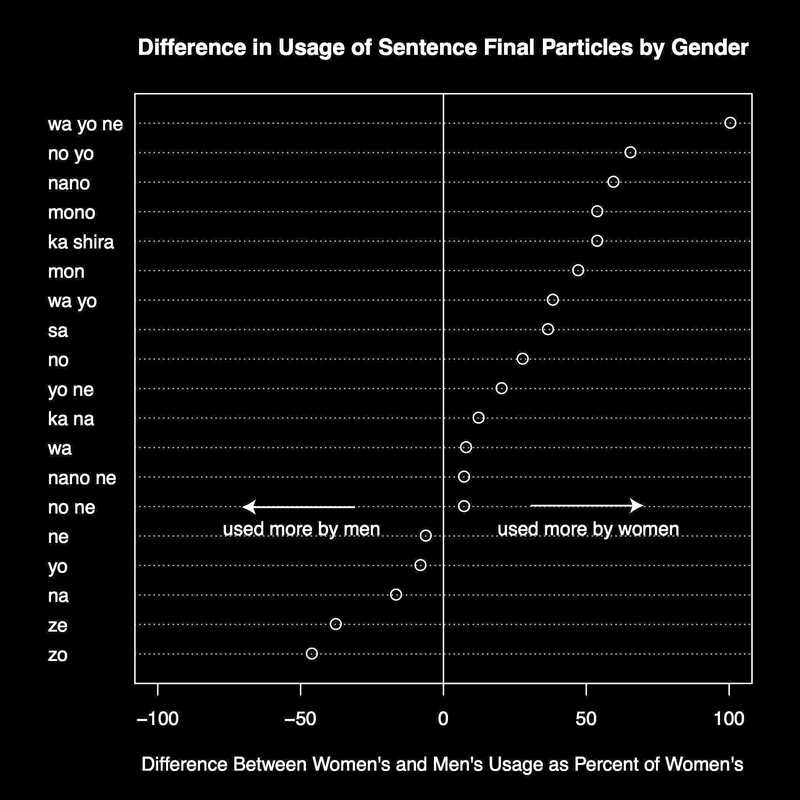

Overall, the difference between male and female usage was very slight. The

ranking of SFP’s by usage rate is very similar for men and women: frequent

particles were used frequently and infrequent particles---generally the most

stereotypically gendered---were used infrequently by men and women alike. The

above figure displays the percent difference between male and female usage rates

for each particle. The traditionally masculine ze and zo are still used

about 50% more by men than by women, and the stereotypically feminine ka shira

and declarative nominalizers mon(o), nano, and no complexes are used about

that much more by women than by men.

Discussion

While the traditional gender differences are evident in these data, men and women do use oppositely-gendered SFP’s. In a similar finding to

Okamoto (1997), women on Twitter use moderately masculine forms

like sa more frequently than strongly feminine particles. But moreover, while

Okamoto found only token use of strongly masculine forms like zo, these data

show that zo and ze together make up a very noticeable 3% of women’s SFP

production.

While it has been recognized that women can use zo when speaking to

themselves, which the broadcast nature of tweets may well resemble, these data

show that women’s usage goes beyond the realm of self-talk. Twitter implements

a form of public conversation with the practice of at-replies: one user can tag

another in a tweet by preceding their username with an at sign. These replies,

while not broadcast to a user’s followers, remain public as standard tweets. Of

the 42 examples of zo used by a female user, 28 of them were used in tweets

which specified an addressee in this manner. It is clear that on Twitter women

can and do choose to use zo despite, or perhaps because of, its assertive

meaning and masculine indexicality.

The reverse case, men using stereotypically women’s SFP’s, is also present in

these data. Wa, which Ide (1979) found to be used by women and

indexical of femininity, comprises solidly 5% of SFP’s used by men; this is only

very slightly less than women’s 5.4% rate of wa use. Complex nominalizers

which soften an assertion or a question are also found to be used by men at

substantial rates: no ne is used by men only 6% less than it is used by

women, and while the difference is greater for no yo, it is not absent in

men’s tweets. Even the most stereotypically feminine SFP, ka shira, is seen

three times in men’s tweets, of which no occurrences were in quotation or read

as sarcasm. Clearly the meaning of the particle, equally an admission of

ignorance as an expression of doubt, is useful for men on some level.

Conclusion

While there is a language ideology and a significant research tradition which views Japanese sentence-final particles as strongly indexical of, and indeed limited to one gender, this study shows that the stark distinctions do not capture the whole picture. Overall the stereotypically gendered particles are used very little, but they were used by both genders in posts on Twitter.

It is not the case that SFP’s in Japanese have lost their social meaning or gender indexicality in tweets. The frequency differences for the most gender-influenced SFP’s are certainly large enough to be salient. Rather, men and women are shown to wield gendered language as a tool, making use of the varied functions and connotations of both masculine and feminine SFP’s. Indeed, this study demonstrates that sentence-final particles can be used quite freely in Japanese for the performance of gender in online discourse.

Bibliography

- Burger, John D., John Henderson, George Kim, & Guido Zarrella. (2011). Discriminating gender on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2011 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (pp. 1301–1309). (Link)

- Fengping, Gao. (2005). Japanese: a heavily culture-laden language. Journal of Intercultural Communication, (10). (Link)

- Ide, Sachiko. (1979). Daigakusei no hanashikotoba ni mirareru danjo sai (Sex differences in the speech of college students). In Monbushoo kakenhi tokutei kenkyuu gengo chuukan hookoku (Interim report of the ministry of education special research grant in linguistics). Tokyo: Ministry of Education.

- Jugaku, Akiko. (1979). Nihongo to onna. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

- Kawaguchi, Yooko. (1987). Majiriau danjo no kotoba: Jittai choosa no yoru genjoo (The intersecting speech of men and women: The current situation as assessed by survey). Gengo Seikatsu (Language Life), (429), 34–39.

- Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyuujo (The National Language Research Institute of Japan). (1951). Gendaigo no joshi jodooshi — Yoohoo to jitsurei (Particles and auxiliary verbs of Modern Japanese — Use and examples).

- Kose, Yuriko Suzuki. (1997). Japanese sentence-final particles: A pragmatic principle approach (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). (Link)

- Masuoka, Takashi. (1991). Modaritii no bunpou (Grammar of modality). Tokyo: Kuroshio.

- McGloin, Naomi Hanaoka. (1997). Shuujoshi (Sentence-final particles). In S. Ide (Ed.), Joseigo no sekai (The world of women’s language) (pp. 33–41). Tokyo: Meiji Shoin.

- Okamoto, Shigeko. (1997). Social context, linguistic ideology, and indexical expression in Japanese. Journal of Pragmatics, 28, 795–817. (Link)

- Reynolds, Katsue Akiba. (1985). Female speakers of Japanese in transition. In S. Bremner et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the first Berkeley Women and Language Conference (pp. 183–196). Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Women and Language Group, Linguistics Department, University of California. (Link)

- Sperber, Dan & Deirdre Wilson. (1987). Precis of relevance: Communication and cognition. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, (10), 697–754. (Link)

- Suzuki, Ryoko. (1990). The role of particles in Japanese gossip. In Proceedings of the sixteenth annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 315–324). (Link)

- Yukawa, Sumiyuki & Masami Saito. (2004). Cultural ideologies in Japanese language and gender studies. In S. Okamoto & J. S. Shibamoto Smith (Eds.), Japanese language, gender, and ideology: Cultural models and real people (pp. 23–37). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Link)